“Never tell people how to do things. Tell them what to do and they will surprise you with their ingenuity.”

-- General George S. Patton

-- General George S. Patton

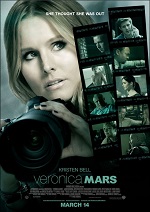

Veronica Mars

Veronica Mars Even though its notable examples number exactly 2 (Veronica Mars and Wish I Was Here), Kickstarter has been one of the biggest changes in how a movie can be made. The crowdfunding site (one of 32 listed on Wikipedia, but inarguably the largest) has definitely been gaining steam as a film funding platform as both those examples were funded in 2013. No longer just the realm of student films and documentaries, legitimate Hollywood talent is getting their movies made with Kickstarter funds, but it has its drawbacks. For example, there's no requirement for project creators to give their funders anything for their investment, though there are plenty of notable exceptions to that. Still, plenty of projects have been pulled after being at least partially funded for various policy or copyright violations, leaving its contributors with nothing but the feeling of throwing their money into a well. The benefits are clear: the crowd has complete control over which projects are deemed worthy of funding and advancement, but what if we could take it a step further? What if we could actually buy stock in a movie?

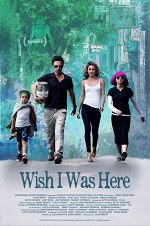

Wish I Was Here

Wish I Was Here It isn't as preposterous as it initially sounds. Think of it as an IPO in the business world, just skewed for film. It would still be the same basic idea: trading ownership stake for funding, except instead of a small, private company looking for an influx of capital to expand their operations, we're talking about prospective films looking to fund their production. Imagine a wide range of films, from some with just a writer and a script, to some with full production crews whose funding just got cut. Now imagine those films all need a funder and the studios aren't returning their calls. You can just run a search "greatest films never made" and spend the next hour reading about amazing sounding projects that fell through for one reason or another. Plenty are for reasons other than funding, but still, what if we could rescue the ones that just needed the money? Heck, Avatar was almost one of these, with James Cameron wanting to make it in 1999 for a staggering $400 million. While this is obviously an example that couldn't have been crowd-funded, it shows the caliber of movie that can get declined for budgetary reasons and how successful they can be once they're actually made.

MGM Studios

MGM Studios It would be up to the "investors" to decide which projects sounded worthy of funding, but that's no different than stock market investors having to decide which companies are worth buying stock in. You could end up with nothing, or you could end up with a small stake in an instant classic. If such a process were ever to happen, it would start with the same sort of small-scale projects that Kickstarter has recently been funding, but I want to paint a little scenario for you. It's the mid-2000's and you're MGM. You're in some pretty massive financial trouble (around $2 billion in debt) which of course is a catch-22. It's tough to get movies funded, and thereby make money, when you've proven you're a bad investment. You've got some valuable properties you own the rights to, but you just can't get squared away enough financially to actually make movies off them and reap the rewards. So projects like a 2010 RoboCop movie directed by Darren Aronovsky (Requiem for a Dream) and written by David Self (Road to Perdition) get scrapped. Now here's where things would get interesting.

A failed movie

A failed movie Suppose Aronovsky and Self approach MGM and say "Look, we really believe in the project we've got here, but everyone in the room knows you don't have the money to make it. Instead of 100% responsibility for funding the production and 100% ownership of this movie's profits (I know that isn't how Hollywood works, but we're simplifying for the example I'm making) we'll let you keep 25% ownership of the profits with the kicker that you don't have to put up a dime. After we make our movie, the rights fully revert back to you, so if you've got your affairs in order by then, feel free to make a sequel or reboot or whatever you want." The team then takes their vision to the masses and sells off the 50% ownership that remains after they've set aside 25% for themselves and their cast and crew. Believe me, it would've raised money: there was plenty of anticipation around this project back in 2008 when it was announced, and loads of disappointment when it languished in development hell. If you're thinking potential damage to the brand would scare studios off this model, keep in mind that Man of Steel was a reboot just 7 years removed from Superman Returns. The Hulk didn't work? Wait 5 years and release The Incredible Hulk (a naming convention borrowed by The Amazing Spider-Man to reboot Spider-Man, also with a fast turnaround). This means there would essentially be zero risk for the studio involved in that deal or another like it: the movie's a success? Great! Free money and you can make your own sequel that stands on the back of greatness! It isn't? You're out nothing and retain the rights to try to make a better one yourself later with almost no modern stigma attached to quickly starting from scratch on a story. Specific to this example, if Aronovsky's RoboCop didn't work out, MGM can still pocket a little cash and crank out its own middling 2014 version. If it does, that sort of risk-free money would've been a great tool to help the embattled studio recover.

Potential

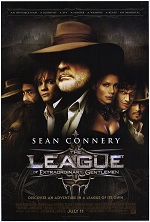

Potential I used RoboCop for this example, because it's latest incarnation is fresh in my mind, but even just sticking with MGM, we could've had a crowd-funded James Bond, Terminator, Poltergeist, the list goes on and on (those three specifically all had failed movies planned). Now expand the list to include any properties whose rights are currently just languishing at a studio uninterested in making them. The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and Spawn come to mind. Imagine the water cooler conversations that would happen amongst Hollywood bigshots if they knew that almost nothing was off limits; that any film could at least be discussed with studios. Of course, this is only scratching the surface. Original ideas with no current rights holders would be a new Wild West of film. Movies for reasonable budgets would spring up constantly with the occasional blockbuster when enough A-list talent was involved to draw people's attention. It could mean the death of the traditional studio system. But there's a giant hurdle to overcome in this scenario: studios are not only responsible for the production, but also the distribution of the finished product. With no studios in place, how would theaters know, or have any way to decide, what movies they showed on their screens? The advertising budgets a major studio release are afforded lets theater owners know that customers will know about the films. Crowd-funded movies may have a bit of money left over for advertising, but odds are, any increase in "share price" would just result in a higher budget for the actual production.

My Rant in a nutshell

My Rant in a nutshell I would argue that in the age of 1080p televisions with Dolby 7.1 Surround Sound (and the increasing advent of 4k televisions, with clarity 4x as sharp as 1080p) are we really so sure that theaters aren't a dying model and we just haven't noticed yet? Other than overpriced food and drink, sticky floors, and potential annoyances from other patrons, what do they really bring to the table? Oh wait, those are all drawbacks? Well in that case, perhaps traditional distribution of the movies isn't such a hurdle after all. And so, at long last, I have led you circuitously to my magnum opus: a company that handles not only the crowdfunding end of these projects, but the distribution as well. Netflix has shown that one can both create and distribute content, so imagine a Kickstarter front-end combined with a Netflix backend that allows members to both buy stake in projects and view the movie on a pay-per-view or purchase model. Conceivably a membership model would also work, with percentages of dues divvied up based on views. Of the Top 10 at the Box Office this past weekend, 4 of them have budgets of $25 million or less. 3 of the 4 made back their budgets in their first week of release and that's just this week as a random example. These are the types of situations that, when framed as investments, make venture capitalists salivate. The only thing missing is the infrastructure. It will take an entrepreneur and a lot of capital to build the company I'm talking about, so a more likely route would be the adoption of the model by an existing company. Considering I could do an entire rant on Qwikster (at one point Netflix wanted to split its services into a company for movies-by-mail and a company for streaming that would require separate memberships), it would most likely come from a source I'm not expecting, with stronger leadership than that. Because of this, let's not hold our breath, but as a movie fan who believes diversity only helps the medium, it's certainly fun to think about.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed