“Every saint has a past and every sinner has a future.”

-- Oscar Wilde

-- Oscar Wilde

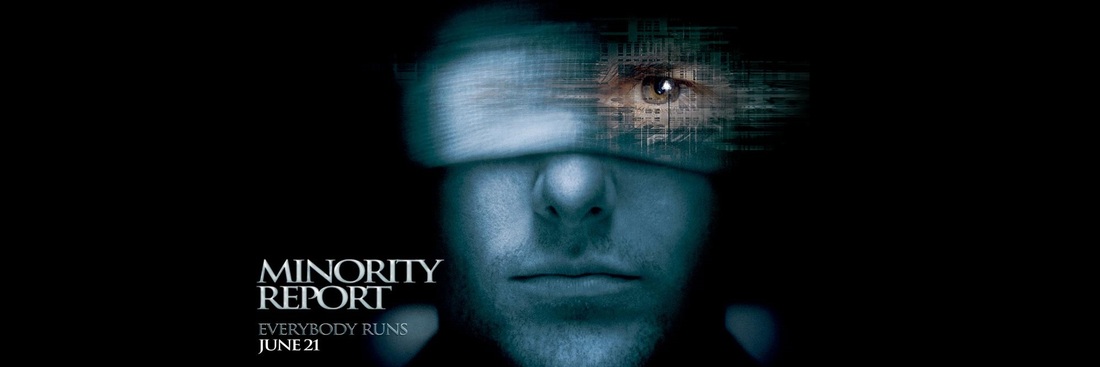

Cruise as Anderton

Cruise as Anderton Minority Report is a science fiction masterpiece released in 2002, that is often overlooked despite its expert handling of a near-future setting. Why? Because of complaints that the ending is too saccharine; a product of star Tom Cruise and director Steven Spielberg not wanting the film to be too dark. In reality, that ending now feels like a carefully orchestrated trick played by Spielberg on the audience and perhaps Cruise himself (he sells the ending better than I think he could've had he known it was tongue-in-cheek). That leaves you with an ending that's actually incredibly dark, cinematography reminiscent of the noir genre, a breakout role for Colin Farrell, and a central plot point to make your head hurt the more you think about it.

**WARNING: MINOR SPOILERS AHEAD**

**WARNING: MINOR SPOILERS AHEAD**

Farrell as Witwer

Farrell as Witwer Cruise stars as John Anderton, the lead "detective" in an experimental unit of law enforcement called Precrime. Using the gifts of three "precogs", led by the strongest, Agatha, who are capable of seeing violent crime before it happens, Anderton's unit has dropped the murder rate in Washington, D.C. to zero. Though the alleged perpetrators proclaim their innocence of crimes they haven't yet committed, Anderton rationalizes this by saying these crimes are no more uncertain to occur than gravity dropping a ball to the floor if it rolls off a table. In other words, once the events leading up to the crime have been set in motion, the outcome is assured. The U.S. Attorney General's Office is thankfully more than a little concerned about this take on determinism as it relates to criminal justice, and so sends Danny Witwer (Colin Farrell), a man more interested in deposing Anderton and taking his glamorous job than in disproving Precrime's functionality. The means to his coup are handed to him on a silver platter when Anderton himself is foreseen to commit the murder of a man he's never even met.

von Sydow as Burgess

von Sydow as Burgess Of course, all of this is not as simple as removing the corrupt leader (though Anderton has Lamar Burgess, played by Max von Sydow, as his superior in Precrime, he is undoubtedly its heart) of a government agency, but it will take the entire movie to sort it out, especially as the perpetrators and their motives vary wildly from the original Philip K. Dick short story. Along the way, Cruise utilizes his "man on a mission" skills to great effect, and other than a misguided attempt at surrealism with a back alley surgeon, the movie doesn't take many notable missteps. Spielberg's vision of the future, however, distracts from these minor flaws as it is one of the most fully realized, if a bit fantastical given it's proximity to the present, ever presented in film. Through consulting with 15 scientists in a 3-day "think tank" Spielberg crafted a future that has already proven prescient on several points (the capabilities of Microsoft's Kinect definitely resemble the Precrime interface) and several firms claim to be close to other technologies shown in the film, with releases well before their 2054 deadline.

Morton as Agatha

Morton as Agatha The drawback to all of this though, is the nagging idea of Washington's cityscape changing that drastically in just over 50 years. 12 years into the timeline and we look to be falling behind Minority Report's vision. That's a complaint that can be levied against even the titans of the science fiction world (1984 and 2001: A Space Odyssey even being bold enough to put the year in their titles) though, so the only relevant concern with the movie is it leaving something on the table by not fully exploring the central question it wants to ask (something that could have easily been given more screentime with a trimming of the aforementioned surrealist scene).

**WARNING: MAJOR SPOILERS AHEAD**

**WARNING: MAJOR SPOILERS AHEAD**

Morris as Lara

Morris as Lara At its core, Minority Report is about free will vs. determinism. We get some other themes along the way, but they're just window-dressing to the same idea that was at the root of Dick's original story. We learn late in the movie that Anderton has been set up by his own boss, Burgess, who fears Anderton's personal demons over the loss of his kidnapped son might bring down Precrime. He accomplishes the "frame" by paying a lowlife to have pictures of Anderton's son splayed about his hotel room and when confronted by Anderton, say he took the child. Burgess realizes the emotion Anderton will feel in that moment, believing himself to have found his son's abductor will force him into the commission of the murder. The movie glosses over a crucial point in all this, however. Anderton will only murder this man because he finds this setup, and he will only find this setup because he's been told he will murder this man. This sort of closed-loop paradox is central to the plot because Burgess takes no action beyond paying the lowlife and giving him the pictures. Pictures of a child in a random hotel room somewhere in the city would do nothing to spur on the commission of a crime, and yet that is all that's required to set the movie's plot in motion. Plenty of other movies are guilty of this oversight as well (in The Time Traveller's Wife, Eric Bana randomly travels to moments in time that have deep emotional meaning to him, yet they only have that meaning because he travelled there in the first place), but I would have expected better from Spielberg. I actually like the inclusion of that element, I would've just preferred it had been explained.

Cruise as Anderton

Cruise as Anderton The movie's real coup, however, lies in its ending. The critics that said it was too light an ending for the material that preceded it had ammunition when the movie was released in theaters. In the end, Anderton reveals Burgess's treachery, the precogs go on to live a life in a secluded cabin free from their visions of violence, and Precrime is dismantled; its convicts set free, having never actually committed a crime. The only downside to this is that Anderton's voiceover admits that murder has returned to the nation's capital. This last bit is important because once the movie was released on home media, it had been removed. So how does making the ending even more one-sidedly positive undermine its critics? Early in the movie, we're told that the convicts of Precrime get "haloed", a band placed over the head that makes the detainees physically docile, but allows their mind free reign. The jailer even comments that they just dream the rest of their lives away. The movie's tonal shift occurs the instant Anderton himself is "haloed" for his crime and placed in that jail. Suddenly, the mastermind Burgess makes a completely unnecessary slip that reveals his villainy to Lara, Anderton's ex-wife! She breaks into the prison using Anderton's eyeball (he had them switched in the back alley surgeon scene to avoid detection) that conveniently still opens all the doors in Precrime! She also calls in favors with Anderton's old team, who are more than willing to risk imprisonment themselves to help their discredited and disgraced boss! At no point are alarms tripped alerting anyone that Anderton has been released!

Spielberg and Cruise

Spielberg and Cruise The point I'm trying to make is that it's much more likely that this entire scenario takes place in Anderton's mind. Nowhere in this narrated ending is there mention of a trial for the murder he committed, as would've undoubtedly occurred, since the only corroborating testimony he has that the lowlife sort of killed himself is from a drugged-up, severely mentally scarred woman who hadn't been fully conscious in years. The only logical explanation, especially given the removal of the one line that somewhat muted the critics, is that Spielberg pulled a fast one on everybody. He slipped a terribly depressing ending past the entire audience and pawned it off as uplifting. For that reason alone, Minority Report deserves a spot in the Pantheon of Spielberg's best.

A visionary sci-fi film that misses perfection because of incomplete exploration of its theme

RSS Feed

RSS Feed