“The animatronics now are certainly more lifelike than before. They've advanced in exactly the same way as the CGI has. It is all really out of my area of expertise, but it definitely made my job a lot easier to act to something that was a lot more expressive, more real.”

-- Sam Neill

-- Sam Neill

Her's "Alien Child"

Her's "Alien Child" CGI has progressed to the point where filmmakers have tough choices to make on things the moviegoer may never think about. Do we actually crash a car, or just CGI it? Do we use a snow machine and location scout, or do we just CGI in the flakes over what we shoot on a soundstage and tell wardrobe to dress the actors warmly? This means that plenty of movies without superheroes or aliens probably use more CGI than you'd think. But for every Gollum, there's a Jar Jar, for every Steven Spielberg who tends to get it right, there's some hack deciding to unconvincingly CGI a presidential motorcade (Olympus Has Fallen; why, Antoine, why?) for no conceivable reason. A lot of the problems stem from the relative cost of CGI. In plenty of cases now, it would cost more to get the actors and drivers on a location-scouted set for the previously mentioned motorcade. It's much cheaper to just shoot on a soundstage and CGI the establishing shots of cars driving along a snowy road. The problem, however, goes far beyond that.

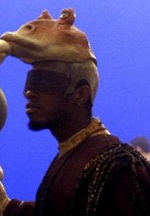

Jar Jar Binks on set

Jar Jar Binks on set To paint in broad strokes, a lot of it comes down to the age of the filmmakers (although obviously not always). When a relatively-young Spike Jonze uses it, it's seamless and plays perfectly in the scene. Her is a great example: you were thinking about the video game character Joaquin Phoenix was interacting with and not the fact that it was, in the movie, a holographic projection of a video game. "Alien Child" adds to, rather than detracts, or even just remains neutral to, the experience of the film. The problem that character overcame is a central one to mixing CGI and live-action: what do you do on-set? Gollum works because the actors could still play off of Andy Serkis. He may have been done up in a motion capture suit, but they could still lock eyes with him, shut out all the rest, and act. It is a much larger leap to Jar Jar Binks: "Please, ignore the blindfolded man, and interact with the hat he's wearing." I can't find an explanation for the blindfold, but it was either to make the CGI process easier (potentially easier to paste over a blindfold than eyes) or to prevent the actors from subconsciously maintaining the wrong eye level for the character. If I had to pick one though, I'd lean towards the latter. So much of acting is REacting to what your co-stars are doing. To deliver a performance based solely on your impression of the scene is the mark of a bad actor and is often described as a "lack of chemistry".

JP model painting

JP model painting What this means is that when a filmmakers overuses CGI, it is perhaps not because they're the talentless idiots it's so easy to categorize them as. Especially in the case of George Lucas, perhaps they're just dreaming too big and losing sight of what will work on-screen. This isn't to excuse those filmmakers however; they should be no more revered than Icarus, cautionary tales for aspiring filmmakers considering the use of CGI. The quote to lead this Rant is from Sam Neill's time on Jurassic Park, directed by the aforementioned Spielberg who always keeps the focus on his players and not the CGI around them. Though JP was a mix of animatronics and CGI, when the scene called for heavy interaction, Spielberg erred on the side of the real, giving his actors something tangible to play off of. Was this more expensive? Probably, although the difference wouldn't be as large as today, but it was inarguably worth it. Compare that to Jar Jar Binks who noticeably lowers the performance of the other actors in scenes with him because they have no frame of reference.

Inception's practical effects

Inception's practical effects CGI has progressed, but not to the level where it is interchangeable with reality. This is not to say that we should retreat entirely from CGI. When shooting The Avengers, I can't imagine animatronics and men in suits would work for the flying aircraft carrier or the Hulk. It is to say that we're not quite as far along as some filmmakers seem to believe. When simulating machines or spacecraft or pretty much anything not alive, CGI can do incredible work these days. When it comes to living things, however, we haven't yet crossed the Uncanny Valley, a term for the idea that the closer we get to lifelike movement and emotion without actually equaling it, the more discomfort the viewer experiences. In these areas, the eyes still aren't quite right, often appearing too glossy, the flesh looks too rubbery, without the varying degrees of elasticity of actual skin, and the light still never hits them quite right to let you forget you're watching a computer's creation. This is why we've almost come full circle to where practical effects are now the realm of the true auteurs. Like Inception, opting for a giant rotating set for its memorable weightless fight scene, or Gravity with "Sandy's Cage", a giant rig Bullock was loaded into every day to shoot her scenes. What does it all mean? It means the newness has worn off of CGI, and that its use is now being judged more appropriately with other aspects of the film. It means that audiences should be harsher when a film opts for poor CGI over better practical effects (I'm looking in your direction, Twilight). Most of all, it means films should be penalized for unconvincing CGI just as much as anything else that prevents you from suspending disbelief.

Bullock in Gravity

Bullock in Gravity It's not a black-and-white issue, however. The slight pullback from its use isn't just a "market correction" for CGI's value. There are impressive ways CGI is being used that expand not just what filmmakers can put on screen, which is what most people see as the advantage, but how films are made in general. Movies like Sin City and Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow were shot almost entirely on green-screen, with everything but the actors (and in Sin City's case, occasionally even the actors) spliced in later. This allowed for relatively modest budgets of $40 million and $70 million respectively, in spite of their star-studded casts. Grandiose ideas like these, being filmed for budgets the studios can swallow opens up the possibilities for filmmakers in a way that wasn't possible even just 20 years ago. That is why CGI will truly come of age when two things happen: we cross the Uncanny Valley into effects indistinguishable from reality (although with the increasing acceptance of 4k televisions, the gap just got wider) and when filmmakers see CGI not just as a replacement for practical effects used for certain elements of a scene, but an alternative to them; an entirely new canvas upon which to paint the scene, a method that allows for the creation of a unique visual style on a more modest budget. As Hollywood is forced to search for new and innovative ways to make their movies, this second aspect will become more prominent, and moviegoers everywhere should cheer anything that creates more diversity in their films.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed